For decades, Hollywood has framed Black women through narrow and often damaging stereotypes – they are put in the background, made voiceless, or hypersexualized figures defined by their relation to white protagonists (or masters). They were rarely granted central roles in action or historical films. The Woman King (2022), directed by Gina Prince-Bythewood, starring Viola Davis as General Nanisca repositions the black female warrior at the center of this film as both an emotional and narrative anchor. By placing a mature, dark-skinned woman as a leader of an all-female African military regiment, this film redefines what heroism, femininity and leadership look like in mainstream cinema by going against all the norms in almost every aspect.

General Nanisca, leader of the Agojie – an elite regiment of female warriors in the African Kingdom of Dahomey – is both fictional and historically grounded character. She embodies physical and moral strength, strategic intelligence, and overall leadership. Viola Davis’s portrayal infuses the character with dignity and emotional depth rarely afforded to black women in action roles, or any roles at all. As Modupe Labode argues, African women in Western media were historically “symbolic of difference and danger, not of self-determination.”1 In The Woman King those associations are reversed: the Agojie are disciplined, ethical, and strategically skilled.

Davis’s performance invites audiences to see black womanhood not as a symbol of servitude, but as the core of leadership and nationhood. This is significant because, as bell hooks observed, Black women have long been denied the right to look, to define, and to act from their own subject position.2 Nanisca’s gaze – calm, directive, and compassionate – asserts that precisely. She does not exist to please, serve, or perform for a patriarchal viewer; she commands both respect and emotional investment.

Nanisca’s body is functional, not fetishized. The camera highlights her physique and movement as evidence of her discipline, not eroticism. In its visual and narrative construction, The Woman King moves decisively away from colonial and patriarchal stereotypes. Yvonne Tasker’s foundational study of female action heroes describes how women’s power is often made palatable through eroticization or irony.3 Prince-Bythewood rejects this aesthetic, emphasizing the realism of bodies in motion: sweat, scars, and labor to replace polish and fantasy.

The film also challenges assumptions about age and femininity (as the prior increases, the latter decreases). Davis, at sixty, performs demanding physical scenes typically reserved for younger actors. Her body is shown as capable and commanding – an image rarely granted to women of her demographic in action cinema. This extends notion of strength beyond youth toward endurance and wisdom.

Furthermore, The Woman King constructs heroism as collective as collective rather than individual. The relationship between Nanisca and the young recruit Nawi reflects what Kristen Warner calls the “multiplicity of black female voice,” where solidarity replaces competition.4 Their journey defies the trope of the lone hero by highlighting mentorship, community, and intergenerational care – qualities that expand on the emotional range of action films.

Representation in media shapes how audiences imagine their own possibilities. Srividya Ramasubramainian’s research on visibility and stereotypes demonstrates that affirming positive portrayals of marginalized groups can increase viewers’ self-esteem and collective pride.5 For Black women seeing Nanisca as a central, multidimensional hero validates identities that have been historically excluded from cinema. The film thus fosters expectations that women – especially women of color – can embody leadership without relinquishing vulnerability or compassion.

Yet The Woman King also faced criticism and backlash. Online commentators accused it of “rewriting history” or promoting “woke feminism”, reflecting persistent discomfort when women, particularly Black women, take center stage heroically. The resistance underscores that Warner identifies as the ongoing “racialized disciplining’ of media voices that challenge normative boundaries.4 Despite such responses, audience testimonies suggest that they film’s psychological impact is largely empowering, offering new imaginaries of black of black femininity grounded in pride rather than pain.

The coming out of The Woman King coincides with broader social movements such as #BlackLivesMatter, which demands recognition of marginalized voices. The film’s production itself – led by a Black female director and with a predominantly Black cast – embodies this shift in authorship and authority. It dramatizes what Labode calls the “reclamation of African womanhood from colonial fantasy.”1

The Woman King stands as a landmark in the ongoing redefinition of who can be a hero. Viola Davis’s Nanisca embodies power rooted in community, history, femininity, and endurance rather than dominance, spectacle, or silence. This film takes apart the colonial and patriarchal gaze by constructing Black women as the author of their own story. While there is still resistance to such portrayals, their very existence signals cultural transformation: Black women are no longer peripheral figures or allegories – they are protagonist whose stories command the audience and the screen. In centering Nanisca, The Woman King transforms both the action genre and the cultural imagination.

Bibliography

1. Labode, Modupe. “From Amazon to Dahomey Warrior: African Women in Western Imagination.” African Studies Review 47, no. 2 (2004): 45–67.

2. hooks, bell. “The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators.” Screen 32, no. 3 (1991): 90–94.

3. Tasker, Yvonne. “Women Warriors: Gender, Representation and Action Cinema.” Cinema Journal 35, no. 4 (1996): 1–25.

4. Warner, Kristen J. “They Gon’ Think You Loud Regardless: The Intersection of Race, Voice, and Media Representation.” Feminist Media Studies 19, no. 5 (2019): 672–687.

5. Ramasubramanian, Srividya. “Media, Stereotypes, and the (In)visibility of Black Women.” Journal of Communication 72, no. 2 (2022): 239–260.

Isabelle Catenaccio

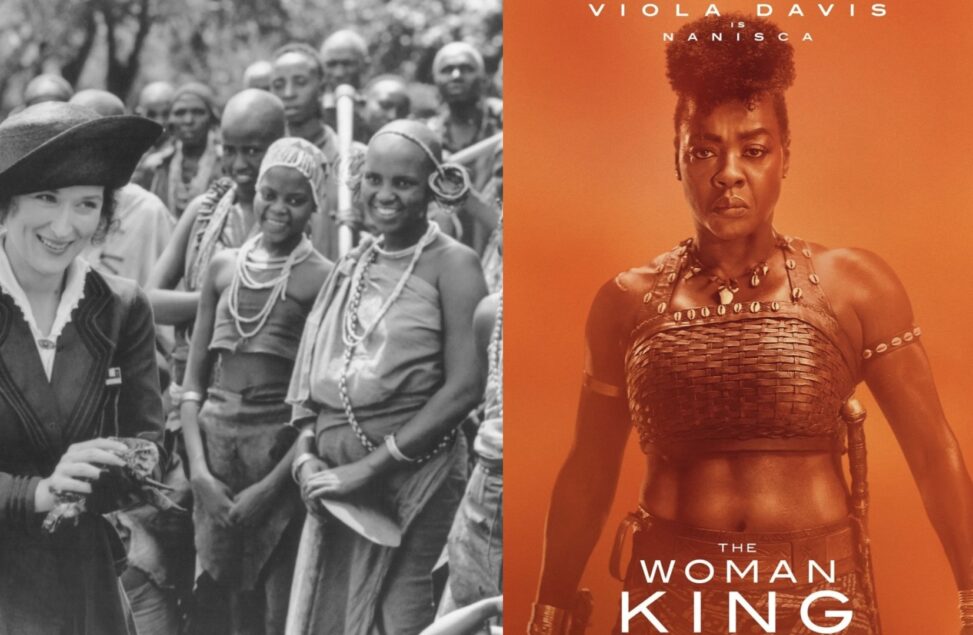

(2) Mariah has done a great job at introducing her main character. She provides not only a background to give us an idea of the strength of General Nanisca, she also goes on to prove how her strength is portrayed through body movement, and notes Viola Davis’s strength in being able to perform such stunts. Mariah argues that Nanisca’s body is not fetishized. Instead, she uses her sources to remind us that realism in terms of the body can be placed on women too. Their bodies do not have to be made palatable for the male gaze. She brings up multiple stereotypes broken in the movie, one being the lone hero trope, recognizing the movie’s mentorship and community aspects. Mariah does a great job at giving us the two perspectives audiences faced when the movie released. She highlights the discomfort some felt as they accused writers and directors of, “re-writing history”, and “woke feminism”. By including this, we sadly see that to some, these stereotypes still very much exist. She brings it to an end by showing us the flipside, where the movie had made impact on those who watched it. As she states, “the Woman King transforms both the action genre and the cultural imagination”. Her statement is backed up throughout her writing as she emphasizes the importance of the Black female director, and the predominant black cast as a shift in the right direction. I believe one picture is from the Meryl Streep movie, “Out of Africa”, while the other is from, “The Woman King”. Mariah doesn’t explain a connection between the photos, or a comparison of the movies. Mariah doesn’t offer a depiction in differences between the same character, rather points out how the depiction of Viola Davis’s character is different than prior depictions of Black women in media.