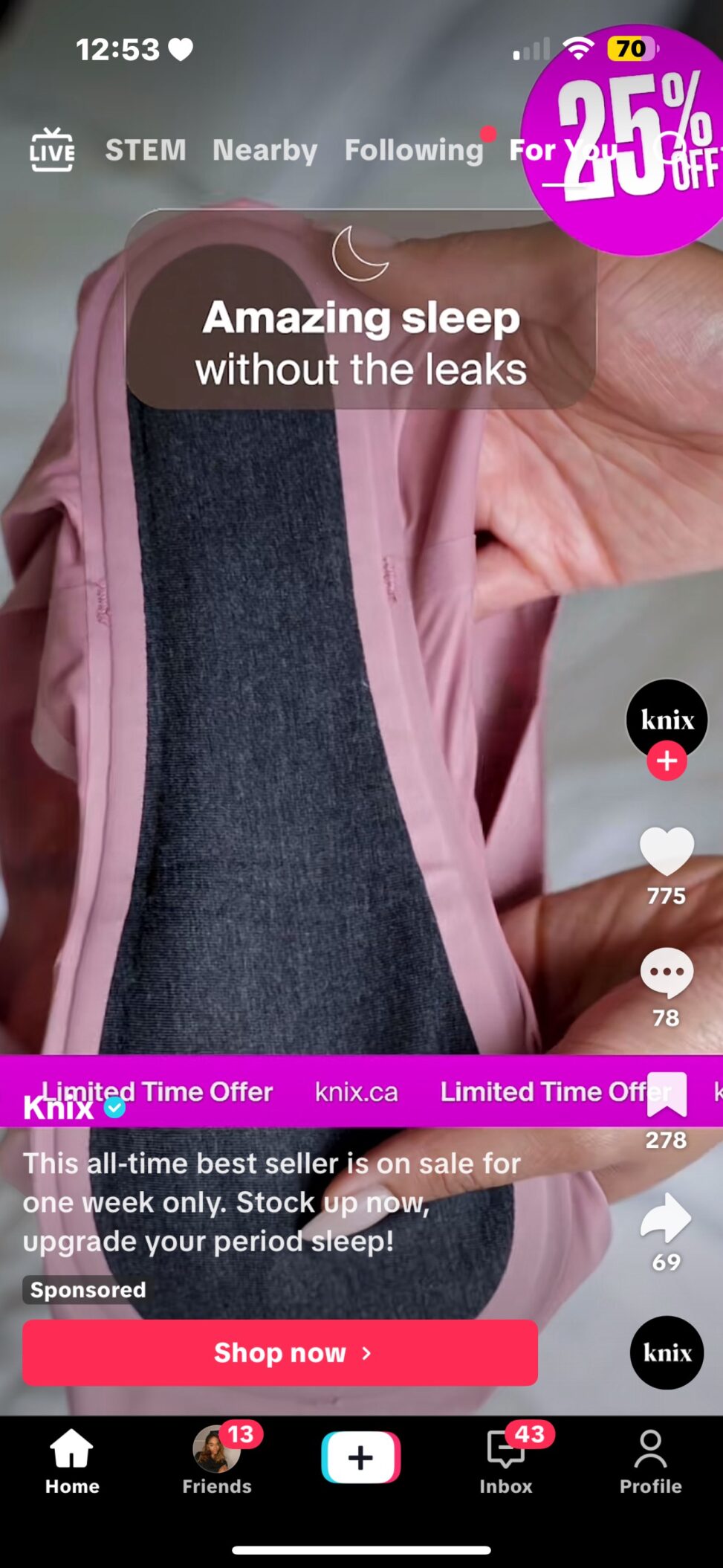

The advert I came across on TikTok by Knix (a Canadian underwear company), promotes a leakproof period underwear as a sustainable alternative to disposable/one-time use menstrual products. This advert comes across as both socially empowering (destigmatizing periods) and ecologically beneficial. This essay will argue that although Knix is portraying its underwear as a sustainable innovation – that it could potentially be, the advert relies more on aesthetic and emotional appeal rather than talking about the verifiable ecological impact.

The main message of the Knix advert is reassurance that menstruating individuals can achieve “amazing sleep without the leaks”. This positions the product not only as functional but also liberating to the individual in the sense that they do not need to worry about leaks and similar anxieties associated with menstruation. Ecologically, the advertisement implies that by purchasing reusable underwear, consumers can reduce their reliance on disposable products such as pads and tampons, which will in turn reduce waste produced from said products. This claim remains implicit rather than the company explicitly stating the ecological impact. The advert provides no direct reference to data, certifications, or environmental impacts. Their ecological impacts are quite vague, which could be described as “associative greenwashing’ where products borrow ecological credibility without substantiating claims through evidence. ¹

This advert is attempting to convince viewers to replace disposable menstrual products with their reusable underwear. It’s trying to encourage and portray a lifestyle where comfort and sustainability go hand in hand. Rather than showing the actual ecological impact of their product and the materials used to make the underwear. They are selling not only a product but a lifestyle: by purchasing their products consumers align themselves with an eco-conscious and body positive mindset. Advertising research has shown that green and eco-conscious marketing often leverages identity-based persuasion, appealing to consumers’ desire to see themselves as a responsible individual that is concerned about the environment. ²

This ad was placed on TikTok, a platform that is dominated by a younger demographic. Its primary audience is menstruating individuals aged around 18 to 40, especially those who are socially conscious, digitally engaged, especially those who are socially conscious as well as easier to influence. By emphasizing empowerment and sustainability, Knix appeals to those who already engage with debates of gender equity, self-care, and eco-responsibility. Personally, as a consumer who is regularly searching for alternative period products, debates on gender equity, the desensitization of periods and ways in which creators are trying to get rid of the stigmatization. Most importantly as an individual that menstruates, I am always looking for the next best product, so I recognize myself as part of this demographic. TikTok’s algorithm, which amplifies content based on engagement, ensures that ads like this one reach viewers that have already shown interest in sustainable or wellness products, reinforcing the targeting precisions of advertising on the application.

Visually the ad relies heavily on close- up imagery of the underwear, highlighting its texture, design and overall comfortability. They go on to show an experiment of an individual with a dropper which is supposed to act as menstrual blood being soaked up thereby evoking a sense of trust in its material durability. The soft color of the underwear in the ad, paired with the moon icon above the phrase “amazing sleep” contribute to a more feminine, soft atmosphere which is calm and comfortable. At the same time, the bright pink they have used to highlight the “25% off” badge creates a sense of urgency to purchase the product which contrasts the calming narrative. From an emotional aspect the advert reassures the viewer that they can sleep without the risk of embarrassment, or the need to wake up to change at night. There is a dual strategy with a contrast aspect – calm comfortable reassurance combined with the urgency to purchase the product at a discounted price. This is a good persuasive appeal for the viewers that are looking for more sustainable products at a cheaper price, as sustainability and good quality usually come at a higher price.

On the topic of whether Knix’s ecological positioning is genuine, it is necessary to look at menstrual products in terms of their environmental impact as a whole. Research from the World Health Organization highlights that disposable menstrual products contribute significantly to global plastic waste, with both tampons and pads taking hundreds of years to decompose. ³ In contrast reusable products such as menstrual cups and period underwear have the potential to reduce waste. A recent study on youth attitudes to reusable menstrual products found that many of them perceive them as both cost-effective and environmentally responsible. 4

This advertisement shows how brands leverage sustainability to market products. While its message of empowerment and waste reduction resonates with consumer values, but the lack of data and details of the actual materials used in the manufacturing of the product lowers its credibility. Green marketing has become more common; it is necessary to distinguish between genuine environmental responsibility and surface-level appeals and promises.

Bibliography

1. de Freitas Netto, Silvio Vieira, Eduardo Sobral Macedo, Mayara Gomes Sobral, and Jesus Manuel Palma-Ruiz. “Concepts and Forms of Greenwashing: A Systematic Review.” Environmental Sciences Europe 32, no. 19 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-020-0300-3.

2. Zhao, Xinshu, and Minhee Kim. “Heuristic Processing of Green Advertising: Review and Policy Implications.” Ecological Economics 203 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107659.

3. World Health Organization. “Environmental Impact of Menstrual Hygiene Products.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization (2024). https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/bulletin/online-first/blt.24.291421.pdf.

4. Newton, Daisy, Clare Southerton, and Karin Hammarberg. “Reusable Period Products: Use and Perceptions among Young People in Victoria, Australia.” BMC Women’s Health 23, no. 78 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02235-7.

Charlotte Oliver

This student’s advertisement submission analyzes a reusable period underwear promoting leakproof period underwear by Knix. This critical stance demonstrates a clear understanding of “associative greenwashing,” where sustainability is suggested but not substantiated.

The student effectively analyzed the greenwashing in the Knix ad, showing how the company promotes its underwear as eco-friendly without real evidence. They used the term associative greenwashing to explain how Knix connects sustainability to emotion and aesthetics rather than proof. By noting the lack of material or certification details, the student showed strong critical thinking, recognizing that the ad relies more on persuasion than genuine environmental responsibility.

This ad promotes its leakproof underwear as sustainable and empowering, but it relies more on emotional reassurance and aesthetic presentation than on proven ecological data. The advertisement is designed for a younger, socially aware audience on TikTok, using empowerment, comfort, and body positivity to connect with viewers and promote a lifestyle aligned with sustainability and self-confidence. While the ad suggests environmental benefits, it provides no concrete information or proof of sustainability, making its claims an example of associative greenwashing, using environmental themes without real evidence.

The student’s analysis was strong, but they could have added more detail about the materials and production process of the underwear to assess Knix’s sustainability claims.

This student had a good use of scholarly sources consisting of De Freitas Netto, Silvio Vieira, et al. “Concepts and Forms of Greenwashing: A Systematic Review.” Environmental Sciences Europe (2020). Zhao, Xinshu, and Minhee Kim. “Heuristic Processing of Green Advertising: Review and Policy Implications.” Ecological Economics (2023). World Health Organization. “Environmental Impact of Menstrual Hygiene Products.” Bulletin of the World Health Organization (2024). Newton, Daisy, Clare Southerton, and Karin Hammarberg. “Reusable Period Products: Use and Perceptions among Young People in Victoria, Australia.” BMC Women’s Health (2023).

Link to students paper: https://visa1500w22.trubox.ca/2025/10/01/knix-reusable-period-underwear/