Following the lives of private spies fighting from dangerous organizations, the Kingsman trilogy has numerous scenes that mix action and humor to make the audience forget what is gruesomely unfolding before their eyes. Kingsman: The Secret Service is the most successful out of the three, with a worldwide gross of $414,351,546 according to Box Office Mojo, more than half coming from international consumers. Given this number, a scene from the film has been chosen to argue the influence of mise-en-scene and editing in action movies.

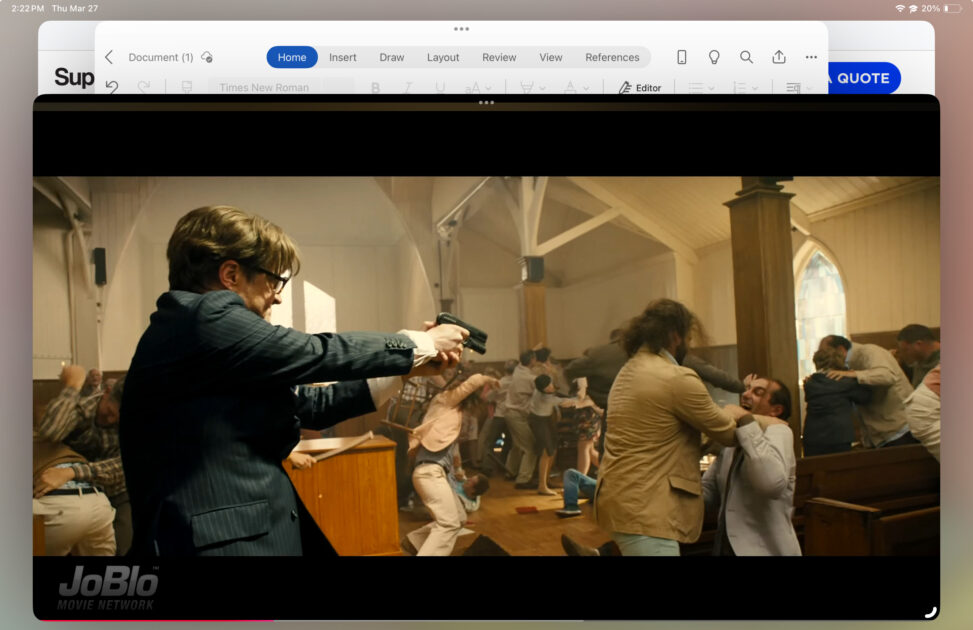

Agent Galahad, played by the White-British actor: Colin Firth, is showed listening to a radical sermon surrounded by white supporting artists. After checking Valentine —the antagonist: played by Samuel Jackson— is not there, he walks to the exit; as this happens, the audience is shown the vile character turning some sort of frequency up, making Galahad lose control and take out his gun to then shoot at a woman cursing him for leaving. By this point, every single person inside the church gives into rage and starts fighting each other. And this is where our one-minute scene comes into play.

From 01:19:09 to 01:20:09, there are 10 noticeable cuts that a non-professional viewer could identify: 42 seconds of uninterrupted violence to then point out the cuts showing the reactions of Galahad’s team —Merlin, the technical specialist agent, and Eggsy, his apprentice— and the two villains. The first three cuts show Eggsy’s grossed out reaction looking at his computer, to Galahad’s point of view, then Merlin’s desperate and confused reaction monitoring the situation. The next cut breaks the 180 degree rule in film, allowing us to see the action displaying in monitor; following those four cuts, the next five show the interaction between the two antagonists, incorporating medium and close-ups shots —also breaking the 180 degree rule— and finally, the minute ends with a shot of the security camera inside the church.

After further investigation of those very graphic 42 seconds, it seems that the editors used invisible cuts for this section of the film. It shows the agent going from the church’s exit to the altar, fighting in a matter the experienced fight choreographer Craig D. Reid described as OHM, meaning One Hits Many. He said: “During an OHM the actor must react to each attack without hesitation. It is easy for an actor to get sloppy, so the stuntman must either time his reaction to the kicks and punches perfectly or let himself get hit” (p. 34), and even thought he criticized American fighting scenes in that paper, it is certain Kingsman took his criticism for the better. Using a handheld camera technique, hidden cuts (whip pans, object obstruction, etc.) and speed ramping in this scene resulted in a very outrageous, graphic and bloody sequence, that lead to contrasting cuts that help the audience recover a little.

The handheld shot, used by filmmaker Wes Andersen is used for this scene with the same purposes in Kingsman. Lee discusses it is for: “the decisive scene, especially tragic moments, [because they] are likely to cause more shock and strong emotions for the spectators compared to other artificial and stylized mise-en-scène” (p. 429). Which is interesting when taking into account that the audience is shown a very controlled and refined environment, meaning the classical spy-movie songs, outfits, and prompts look of the spies, and vibrant, high-contrast lighting.

Blackmore, in The Speed Death of the Eye, discusses the effects of the techniques contemporary movies use to become a blockbuster: “The speed death of the eye works on a number of principles. It moves the eye-camera through space and around objects more quickly than the eye can comprehend” (p. 370); in Kingsman’s case, this happened “saturating the eye with so much detail at such a rate that there can be no maintaining the pace” (p. 370).

The mix of these film elements for sure make this scene better than many, but what are the consequences the graphic content brings to its viewers? In a study where the repercussions of violence in movies were explained, a conclusion was made: “This [referring to the brainwork] increases the difference between the components, thus elevating the possibility of aggressive behavior for the person” (Betsch et al., p. 146). But this is not the only thing to worry about; another study found that “movies with violent content and a story that exerts violence on people and especially adolescents, negatively affect their decision-making and inhibition power, pushing them to make risky decisions” (Ghandali et al. p. 773). Knowing this, the audience must take into consideration the maturity of their children and limit the amount of violent material consumed; remembering that there are other masterpieces that show astonishing use of mise-en-scenè to learn from.

Mutsa Madzivire

The introduction should have been a more detailed summary of the plot. When discussing the Mis scene, the essay clearly understands editing techniques using technical terms such as the 180-degree rule. The essay includes academic sources to provide evidence for their argument. However, you did not expand on how lightning, sound and tone were used to influence audience perceptions. Do not just add academic sources; interpret them and connect them to a particular scene or point in the film. The analysis does not explain the film’s message about violence and society. More analysis is needed on how the film affects the behaviour or opinions of its viewers on violence. The essay could benefit from more cultural context, such as the race and place where the scenes occur. The essay does not flow as ideas are not linked to previous ideas, thus not painting a cohesive narrative.